Problem solving

A guide to problem solving

Foreword

Nick Dean - Chief Constable Cambridgeshire Constabulary

‘Policing our neighbourhoods’ is at the centre of what we do here in Cambridgeshire. We have taken great strides in placing this at the core of our policing model and the future investment in our neighbourhood teams is welcome. The concept of problem solving as the bedrock of policing; the foundation upon which everything else is built. I am a great believer in investing in tackling the cause of issues and in achieving long term, sustainable solutions. A problem solving approach is vital if we are to make a real difference to our communities. Since my arrival in force I have witnessed some fantastic initiatives making a real difference in improving the quality of life of those we serve. However, problem solving is not just limited to neighbourhoods; it should be at the heart of how we approach issues and concerns in whatever field of work we operate.

Very often communities approach us or our partners when they really need help and we have a duty to respond in a positive way. Of course I recognise that we cannot do everything but those key concerns, affecting people’s quality of life, causing harm and distress to communities should be our priority.

We have invested in problem solving training and guidance and this document adds to the reference material already available. Working together with our communities and partners we can make a real and sustainable difference; that is why I am a real advocate of problem solving.

Cambridgeshire is a safe county but working together and with our communities we can make it even safer, protecting the public by getting to the root cause of issues; taking a problem solving approach allows us to achieve that goal.

I look forward to working alongside you to make a real difference.

Crime prevention is ultimately problem solving

Introduction to problem solving

The majority of problems we see seem relatively straightforward on the surface, for example, young people causing anti-social behaviour, and we assume we know how to solve them. Nevertheless problems often fail to respond to our interventions. Quite often this is because we haven’t taken the time to properly understand the underlying causes of the problem. South Cambridgeshire Community Safety Partnership has adopted a problem solving approach that will enable you to have a thorough understanding of problems that your community faces and assist you to identify and address the underlying causes at an earlier stage and ultimately prevent a problem becoming a crime.

The benefits of our approach also include:

- A consistent approach to problem solving across the county

- The ability to better co-ordinate problem solving activity with and between partners

- The identification and sharing of effective practice

- A simple process with minimal bureaucracy

Identifying problems

A problem can be defined as:

- A cluster of similar, related or recurring incidents rather than a single incident.

- An issue of substantial community concern

Or a combination of:

- A type of behaviour

- A place

- A person(s)

- A special event or time

- A specific desirable object or hot product

Most problems can be resolved with straightforward enforcement and/or prevention measures, and the police and our partner agencies are the initial people that are called. Once that call is made there is an assumption that the matter will be resolved. However where a problem becomes more complex, persistent or includes a risk of harm to a victim/community then a problem solving approach is needed.

A complex problem can be described as:

- A complex or persistent issue that cannot be quickly resolved and which requires to coordinate activity from more than one agency (may include neighbourhood priorities) and often the community itself.

- An issue which presents a high risk of harm to a community or an individual (for example, identified through the vulnerability assessment process).

- A regular event which has a significant impact on police/partner resources/the community (for example, mischief at night).

Once identified however a problem must be managed in a structured and co-ordinated way that addresses the underlying causes.

Think of it as an overflowing bath. You can keep bailing out the water but unless you turn off the tap the problem will still exist.

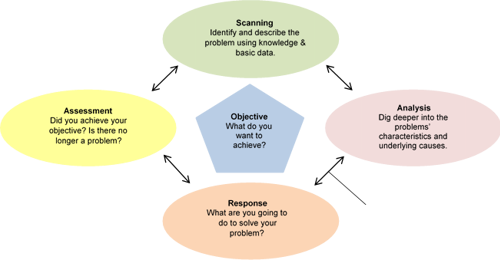

Please see the below interesting video that describes the SARA model - Scanning/Analysis/Response/Assessment.

We have an issue we would like to tackle – what do we do?

The SARA model is a widely used and effective method to help understand the underlying causes of problems, to identify solutions and to assess the effectiveness of responses.

The model above has been part of policing for over 30 years. Whilst it is important to work through each stage of the model the objective stage may become clear once the scanning stage has been completed. The problem solving plan will help ensure that your responses are robust and effective and will provide a clear audit trail.

Scanning

The first stage of the model is to ensure that you know there is a problem and what the problem is that you want to solve. The nature of a problem may appear obvious, e.g. young people involved in anti-social behaviour in a shopping precinct. Nevertheless it is important to clearly and concisely define the problem otherwise responses may become too complex and any action you take may fail to get to the root of the problem.

Scanning will enable you to understand the scale of your problem.

Perceptions of crime/community safety and the realities of crime levels/community safety are very different matters. This stage will help you separate the two.

It may be useful to ask yourself some initial questions to help you define the problem:

- Does the problem actually exist? – If the problem has been reported by someone you may need to check against crime and incident data or by speaking to communities, voluntary groups, partner agencies etc.

- How frequently does the problem occur and how long has it been happening?

- What impact is the problem having on our community, police or other agencies?

- Is anyone else already dealing with this problem? Do they know what I know? Can I give them more information to inform their response.

- What are the risks associated with this problem? – Will the problem resolve itself or does it require intervention to stop it. This will inform the type and level of response.

- What do I want to achieve? – This is a crucial question because the effectiveness of any action you take will be judged against the objectives you set. Whilst resolving a problem may be desirable this will not always be possible. Sometimes mitigating or reducing the effects of a problem through raising awareness of the issue will be all you can do.

The answers to these questions serves to assist the police and other agencies to fully acknowledge the impact of the problem and how we can support you to tackle the issue. If this problem is likely to lead to an enforcement initiative, either civilly or criminally then your initial evidence of the scanning phase can be vital to agencies in progressing matters.

Analysis

Thorough analysis is the key to developing effective solutions. Research should first be directed towards the problem and its causes before you start thinking about solutions, otherwise your actions might not actually deal with the real problem. There are two key elements to the analysis of a problem:

- Understand the problem through research

- Identify possible solutions

Understand the problem through research – Don’t assume you know what is causing it as you may be wrong! It can be useful to develop a working hypothesis about why the problem is occurring but be prepared to challenge and change that hypothesis.

Think of it like an investigation. These questions may be helpful to ask:

- What data is available to help us understand what is happening?

- When is it happening and how often? Are there any key times/days?

- How long has it been going on?

- Where is it happening? What are the features of the location?

- Who is affected and how? Do victims have any common characteristics?

- What events and conditions contribute to the problem?

- What do you know about the perpetrators? Do they have common characteristics?

- Why is it happening? What are the motives of those involved?

- How do the incidents happen? By breaking the problem behaviour down into steps you may that find each step provides an opportunity to intervene.

- What partners should be involved?

- What other resources are available to get a better understanding of this type of problem (e.g. specialist advice, academic research, College of Policing etc.) Once you’ve been able to answer as many of these questions as you can begin to start to solve the problem through analysis of the information. The best tool for doing this is the Problem Analysis Triangle.

This is based on the idea that a problem can only exist if an offender and victim/target are located at the same place at the same time without the presence of a capable guardian. If you take away one element of the triangle then the problem may not occur.

For most problems, changing some elements of the triangle will have more of an impact than changing others would. In general focus on the parts of the triangle that you and your partners can have the most impact on.

From your analysis you will quickly identify these elements, so where offenders are targeting numerous locations and victims, e.g. burglaries then you would mainly target the offenders. But if those burglaries were at repeat locations with repeat victims, then your approach might be to make those locations and victims less vulnerable e.g. target hardening. It may also be necessary to work with other residents to ensure that no further opportunities are created for a returning offender.

See the Problem Analysis Triangle as a useful tool to 'question' each side of the triangle - what do you know about the offender/victim/location. Then ask yourself what may be missing and what would you need to know.

Identify potential solutions – Having gained a better understanding of the root causes of the problem you need to consider possible solutions. It is unlikely that one intervention on its own will solve the problem. It may well require co-ordinated activity by different agencies.

Remember that any proposals you come up with need to be achievable and proportionate to the threat posed by the problem.

Consider the following:

- How is the problem addressed at the moment and what are the strengths and limitations of the current response?

- What powers or duties do the police or others have to deal with the problem?

- What experience do colleagues or partners have in dealing with this type of problem? – meetings or focus groups can identify things you hadn’t considered.

- What other agencies (such as the voluntary sector) might be able to help?

- What can I do to increase the risk for the offender/s (for example, increasing the likelihood of being caught) or reduce the rewards from their crime (like property marking)?

- What can I do to discourage offending behaviour or divert offenders?

- How can I reduce the likelihood of a person/location being subject to crime/anti-social behaviour?

- What examples of good practice are available? - It is likely that someone somewhere has faced a similar problem. There are plenty of resources available to you to find some good practice.

Response

By this point you should have plenty of information about the problem, a good understanding of the threats posed, an idea about what you want to achieve and the powers and options available to you.

The Response phase involves selecting the most appropriate options available and developing an SARA plan. If other agencies are involved in the response then you should develop the plan in consultation with them and be prepared to negotiate. If you disagree on what works or what options to choose then you might need to compromise or try to influence others. It helps to know what resources/ services other agencies have available to them. For example Local Authority teams can access a range of Early Intervention Services, Registered Social Landlords have a host of tools in their toolbox to manage tenants.

Again, SMART can help you choose the most appropriate actions:

- Specific – Those responsible for delivering an action should have a clear understanding of what it is they are being asked to do.

- Measurable – You need to be able to assess whether the activity has had a direct impact on the problem. What output and outcomes do you expect to see?

- Achievable – Setting unrealistic plans can lead to failure, frustration and a loss of victim/community confidence. Whoever is going to deliver the plan needs to have the capacity, resources and powers to do so.

- Relevant – There should be a clear link between the action you take and what you are trying to achieve.

- Time Bound – You should build in regular reviews of your activity and agree how long the activity will run before it is evaluated. The reviews may form part of existing partnership structures, for example problem solving groups.

In addition your SARA plan should:

- Be proportionate – E.g. covert policing tactics or large numbers of police resources may not be justified by the threat posed by the problem.

- Be sustainable - If a constant resource is the solution, e.g. frequent police patrols, then this itself can become a problem, especially if the reason for engaging in the problem solving itself was to reduce the demand on the police/partners.

- Have an exit strategy to move the solution from a police owned and driven response to a sustainable community-owned response.

- Be cost effective - Funding can often be an issue when it comes to responses – a broad, inclusive partnership can often bid to funding streams that the police, as a sole agency cannot. Some funding streams only allow applications from non-statutory bodies – however if, for example, the local church is one of the stakeholders, then they might bid on behalf of the partnership with the bidding skills of the whole partnership being used to compile the bid.

- ‘Think outside the box’ – Innovative (and even bizarre) initiatives have been the basis for proven long-term solutions.

Having identified options that are SMART you need to agree a delivery plan with partners. The OSARA plan should identify who is responsible for elements of that activity.

- Enforcement – What powers can police or partners employ, including investigating offences, pursuing CBOs, tenancy enforcement etc.

- Prevention – Activity can be focused on any element of the PAT triangle, e.g. target hardening a victim’s address, Neighbourhood Watch, imposing curfews on suspects, encouraging offenders to engage in substance misuse treatment etc.

- Information/Intelligence – Sources of information about a problem should be kept under review and new ones identified. This will help to identify any changes in the nature of a problem as well as evidencing the effectiveness of your response.

- Communication – Consider how you will continue to engage with partners to review activity and share information. You should also consider how you will continue to engage with victim/s and the wider community. This will provide reassurance that you are dealing with their problem and will encourage the flow of information.

The OSARA plan and the details of activity undertaken should be shared between partners so that everyone knows what others are doing. In Cambridgeshire Constabulary this will mostly be NPTs who will be used for this purpose by police and information will need to be shared with partners as laid out in an information sharing agreement.

Regular review meetings should be held during the Response phase. Progress against actions agreed as part of the plan should be reviewed, and an assessment made of whether the plan is likely to achieve the overall objectives. If it isn’t you may need to consider revisiting the Scanning phase.

Assessment

Evaluation of the response to a problem is critically important in:

- Determining whether the plan was implemented as intended (if not, why not?).

- Determining whether it had the desired effect (did you achieve your goals?).

- Identifying what didn’t work and any changes needed to the plan. This may involve going back round the OSARA model.

- Identifying what did work as well as recognising and sharing good practice.

If we don’t properly evaluate our response, we can never know if what we have done actually had any effect. This is the case even if the problem has stopped because it may have just stopped on its own and not because of our activity.

The assessment can be done using a variety of data which you will have identified during the scanning phase, for example

- Calls for service – Have they increased/decreased?

- Crime and incident data – Has the problem stopped or simply moved elsewhere or changed in nature?

- Victim/Community feedback – What is their perception of the problem now?

- Media and social media reporting reduced or stopped

Debriefing is an important component of evaluation and should always be included and encouraged at the conclusion of all operations or plans where possible. By involving as many stakeholders as you can in any debrief you will gain a holistic view of what went well, what didn’t go well and why?

The details of your evaluation should be recorded on the Problem Solving Plan and retained. This is so that anyone dealing with a similar case in the future will be able to access the details of your problem.

Consideration should be given to whether your response could be considered as good practice.

This may include:

- Innovative ideas that have minimised the impact or solved the problem.

- Introduction of a scheme / initiative that has solved or minimised the problem

- Exceptional multi-agency work to solve a problem

- Successful use of anti-social behaviour powers/legislation to deal with the problem

Where responses have been successful and represent good practice they should be shared. Partnerships and Operational Support can do this via good practice and may share more widely with policing colleagues on Knowledge Hub, so that others who are dealing with similar problems can learn from your experience. By doing this we will be able to build up a local library of effective practice that will help us deliver a consistent service to victims across the County and improve our overall response to crime and anti-social behaviour.

Identifying good practice also provides us with an opportunity to recognise the good work of those involved. It is a chance for anyone to say thank you and well done or even to nominate someone for a commendation or an award.

10 Principles of Crime Prevention

- Target hardening

- Target removal

- Removing the means to commit crime

- Reducing the payoff

- Access control

- Surveillance

- Environment change

- Rule setting

- Increasing the chance of being caught

- Deflecting offenders

|

Twenty-five techniques of situational prevention |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Increase the effort |

Increase the risks |

Reduce the rewards |

Reduce provocations |

Remove excuses |

|

1. Target harden - Steering column locks and immobilisers - Anti-robbery screens - Tamper-roof packaging |

6. Extend guardianship - Take routine precautions: go out in a group at night, leave signs of occupancy, carry phone - “Cocoon” neighbourhood watch

|

11. Conceal targets - Off-street parking - Gender-neutral phone directories - Unmarked bullion trucks

|

16. Reduce frustrations and stress - Efficient queues and polite service - Expanded seating - Soothing music/muted lights

|

21. Set rules - Rental agreements - Harassment codes - Hotel registration |

|

2. Control access to facilities - Entry phones - Electronic card access - Baggage screening |

7. Assist natural surveillance - Improved street lighting - Defensible space design - Support whistleblowers

|

12. Remove targets - Removable car radio - Women’s refuges - Pre-paid cards for pay phones |

17. Avoid disputes - Separate enclosures for rival soccer fans - Reduce crowding in pubs - Fixed cab fares

|

22. Post instructions - “No parking” - “Private property” - “Extinguish camp fires” |

|

3. Screen exits - Ticket needed for exit - Export documents - Electronic merchandise tags |

8. Reduce anonymity - Taxi drivers IDs - “How’s my driving?” decals - School uniforms |

13. Identify property - Property marking - Vehicle licensing and parts making - Cattle branding |

18. Reduce emotional arousal - Control on violent pornography - Enforce good behaviour on soccer field - Prohibit racial slurs

|

23. Alert conscience - Roadside speed display boards - Signatures for customs declarations - “Shoplifting is stealing” |

|

4. Deflect offenders - Street closures - Separate bathrooms for women - Disperse pubs |

9. Utilize place managers - CCTV for double-deck buses - Two clerks for convenience stores - Reward vigilance |

14. Disrupt markets - Monitor pawn shops - Controls on classified ads - Licensing street vendors |

19. Neutralise peer pressure - “Idiots drink and drive” - “It’s OK to say no” - Disperse troublemakers at school

|

24. Assist compliance - Easy library checkout - Public lavatories - Litter bins |

|

5. Control tools/weapons - “Smart” guns - Disabling stolen cell phones - Restrict spray paint sales to juveniles |

10. Strengthen formal surveillance - Red light cameras - Burglar alarms - Security guards |

15. Deny benefits - Ink merchandise tags - Graffiti cleaning - Speed humps |

20. Discourage imitation - Rapid repair of vandalism - V-chips in TVs - Censor details of modus operandi

|

25. Control drugs and alcohol - Breathalyzers in pubs - Server intervention - Alcohol-free events |